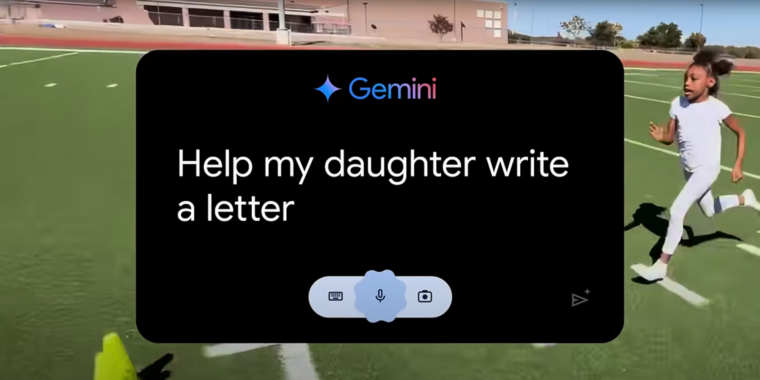

If you’ve watched any Olympics coverage this week, you’ve likely been confronted with an ad for Google’s Gemini AI called “Dear Sydney.” In it, a proud father seeks help writing a letter on behalf of his daughter, who is an aspiring runner and superfan of world-record-holding hurdler Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone.

“I’m pretty good with words, but this has to be just right,” the father intones before asking Gemini to “Help my daughter write a letter telling Sydney how inspiring she is…” Gemini dutifully responds with a draft letter in which the LLM tells the runner, on behalf of the daughter, that she wants to be “just like you.”

I think the most offensive thing about the ad is what it implies about the kinds of human tasks Google sees AI replacing. Rather than using LLMs to automate tedious busywork or difficult research questions, “Dear Sydney” presents a world where Gemini can help us offload a heartwarming shared moment of connection with our children.

Inserting Gemini into a child’s heartfelt request for parental help makes it seem like the parent in question is offloading their responsibilities to a computer in the coldest, most sterile way possible. More than that, it comes across as an attempt to avoid an opportunity to bond with a child over a shared interest in a creative way.

My initial response is the same as yours, but I wonder… If the intent was to comfort you and the effect was to comfort you, wasn’t the message effective? How is it different from using a cell phone to get a reminder about a friend’s birthday rather than memorizing when the birthday is?

One problem that both the AI message and the birthday reminder have is that they don’t require much effort. People apparently appreciate having effort expended on their behalf even if it doesn’t create any useful result. This is why I’m currently making a two-hour round trip to bring a birthday cake to my friend instead of simply telling her to pick the one she wants, have it delivered, and bill me. (She has covid so we can’t celebrate together.) I did make the mistake of telling my friend that I had a reminder in my phone for this, so now she knows I didn’t expend the effort to memorize the date.

Another problem that only the AI message has is that it doesn’t contain information that the receiver wants to know, which is the specific mental state of the sender rather than just the presence of an intent to comfort. Presumably if the receiver wanted a message from an AI, she would have asked the AI for it herself.

Anyway, those are my Asperger’s musings. The next time a friend needs comforting, I will tell her “I wish you well. Ask an AI for inspirational messages appropriate for these circumstances.”

I don’t think the recipient wants to know the specific mental state of the sender. Presumably, the person is already dealing with a lot, and it’s unlikely they’re spending much time wondering what friends not going through it are thinking about. Grief and stress tend to be kind of self-centering that way.

The intent to comfort is the important part. That’s why the suggestion of “I don’t know what to say, but I’m here for you” can actually be an effective thing to say in these situations.

Don’t need to ask an AI when every website is AI-generated blogspam these days